Hassan Fathy's Desert Vision in New Mexico

A sanctuary of Islamic design can be spotted deep within the American Southwest, designed by the legendary Egyptian architect.

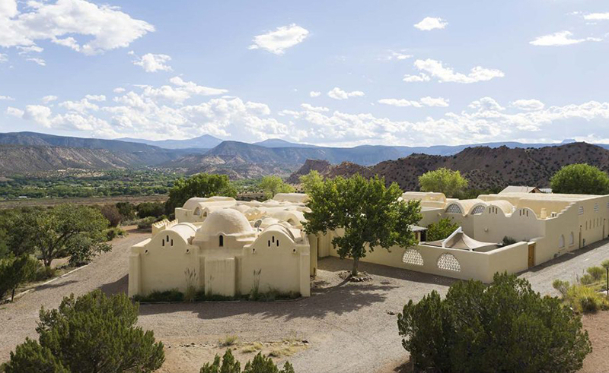

The mesa of Abiquiu rises under New Mexico’s boundless sky in an area known for its intense sunlight, deep shadow, and the vibrant colours of the desert landscape. Here, the Sierra Negra mountains loom in the near distance with jagged peaks softened by a warm light that, as the day wanes, turns a shade close to the deep red earth. The Rio Chama cuts through the rugged land like a ribbon of silver glinting under the sun as it winds past arid hills and through the valley’s vivid greenery. The vast open land, bestrewn with junipers and the occasional sagebrush, stretches far and wide.

To the naked eye, it may seem that the region’s appeal lies solely in its natural beauty, yet within the sprawling desert expanse lies Dar al Islam, an inconspicuous sanctuary for Muslim travellers conceived by acclaimed Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy.

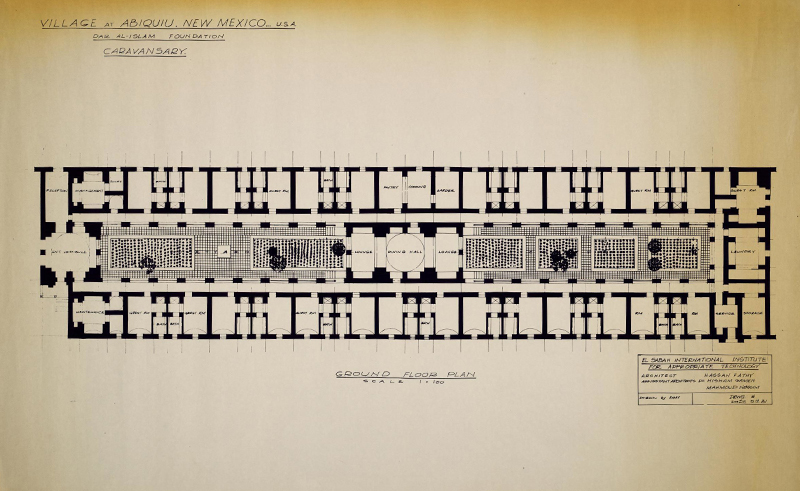

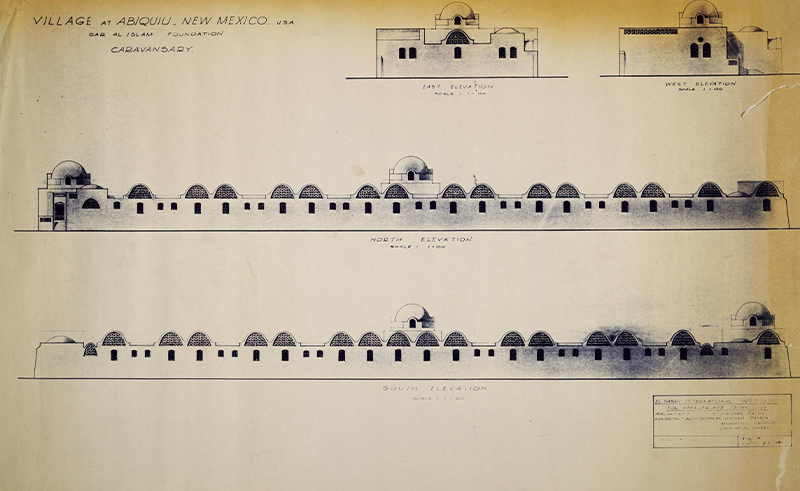

The concept came about in the 1980s. Dar al Islam was intended to establish a vibrant Islamic village, blending worship, education and community life. The master plan included a mosque, madrasa, housing for 150 families, dormitories, a women’s centre, public baths, a hotel, and a crafts centre. For a time, up to 30 families lived there, but financial difficulties by 1990 forced the project to shift from a residential community to an educational and spiritual retreat. Despite the altered scope, the architecture reflects the vision that inspired its creation.

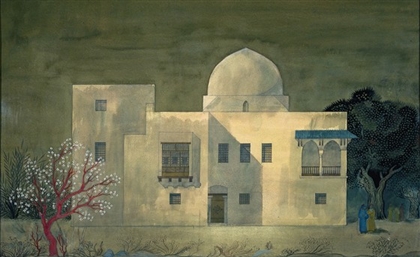

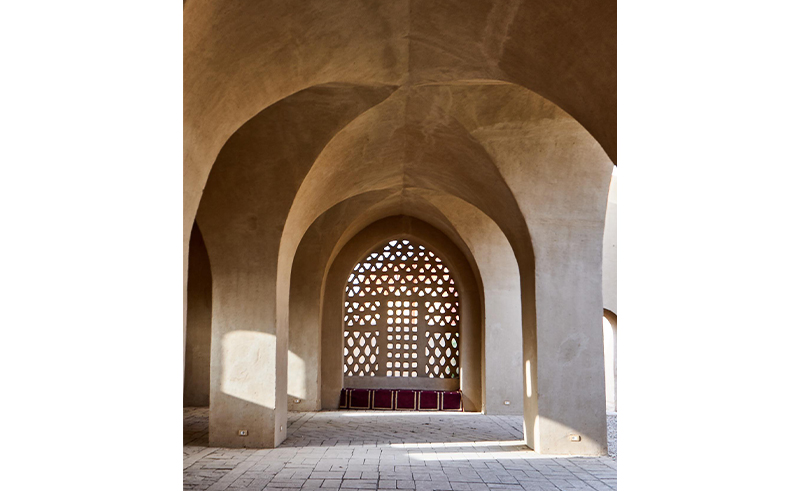

At the heart of Dar al Islam is Fathy’s architectural philosophy, rooted in vernacular traditions that use local materials to harmonise structures with their environment. Fathy designed the mosque and madrasa complex with inspiration from Nubian vernacular architecture, employing domes, vaults and adobe brick to merge Islamic heritage with the rugged New Mexican landscape. He worked pro bono, driven by a desire to bring a distinctly Islamic architectural form to the American Southwest.

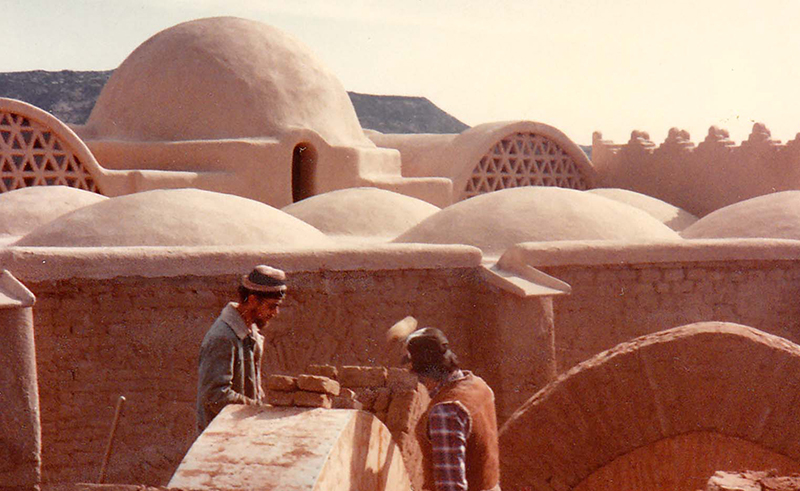

Building in New Mexico’s climate posed challenges unfamiliar to Fathy’s experience in Egypt. To address heavy snowfall and freezing temperatures, traditional adobe was supplemented with small pumice bricks, allowing masons to continue construction in the cold. Vaults and domes were coated with plaster and insulated with foam to prevent condensation, a practical adaptation that nonetheless deviated from Fathy’s ideal of using purely natural materials.

Fathy’s dedication to authenticity extended to the artisanship behind the project. He brought two Nubian craftsmen from Egypt to train local workers in traditional brickwork techniques, ensuring the domes and vaults reflected centuries-old craftsmanship. These architectural elements became central to Dar al Islam’s identity.

Construction of the mosque and madrasa was meticulous but hindered by financial constraints. The mosque was completed without the minaret Fathy had envisioned, while parts of the madrasa remained unfinished when work halted in 1986. For decades, the northeast quadrant stood incomplete, symbolising the unrealized potential of Fathy’s master plan. When construction resumed in 2016, budget limitations led to the use of cheaper materials, introducing incongruities such as Styrofoam decorations and a metal roof that clashed with Fathy’s original vision.

Fathy initially proposed integrating elements of Native American Pueblo architecture to resonate with the local environment, but this idea faced resistance. The project’s leadership favoured Islamic aesthetics, leading to a compromise that retained familiar domes and arches while missing the opportunity to fully embrace the indigenous architectural language of New Mexico.

The funding model, reliant on donations, compounded these challenges. Fathy’s labour-intensive methods, while aesthetically impressive, proved costly, contributing to financial strain and disagreements within the leadership. Ultimately, this led to the departure of key figures and the scaling back of the project’s original design. While the creation that now stands may represent a compromise of vision and material constraint, it still echoes with the cross-cultural ambitions that had laid its foundations.

- Previous Article The Enduring Charm of Jeddah’s Old Town of Al Balad

- Next Article The Brilliance of Basuna Mosque by Dar Arafa Architecture

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026