Bill Willis, The Expatriate Who Shaped Moroccan Modernism

Bill Willis translated the ancient textures of Marrakech into a new dialect of luxury, designing rooms of sublime contradiction for himself, for Marrakesh and most famously for Yves Saint Laurent.

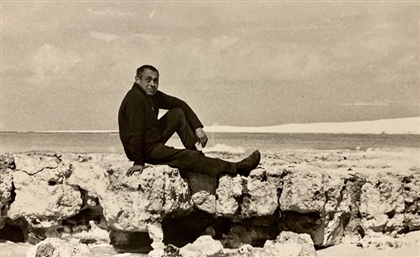

He arrived in Marrakech as so many others did in the gauzy, gin-soaked 1960s—chasing a mirage. But where others saw an exotic backdrop for their indiscretions, Bill Willis, a lanky son of Tennessee with a Beaux-Arts pedigree and a drawl that clung to him like dust, saw a language waiting for a new grammar.

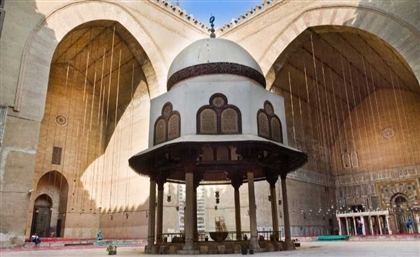

Over four decades, until his death in 2009, Willis performed a peculiar alchemy, taking the ancient architectural lexicon of Morocco—the zellij, the tadelakt, the keyhole arch—to restore, and re-voice it, inflecting its centuries-old sentences with a modern, decadent, and profoundly Western cadence. He became, in effect, Morocco’s most influential interpreter to itself and to the world, a designer who helped a nation see the contemporary glamour in its own past.

Willis’s story germinated in the fertile ground of dislocation. Uprooted from the American South, polished in Paris, and only briefly potted in Rome, he lived as a man of fractures before he mastered the art of fusion. It was Marrakech that provided the current, a jolt of recognition that he would spend a lifetime describing, both in words and in the very plaster of his walls. “My discovery of the Islamic world has been an astounding experience,” he told Architectural Digest in 1989. He had arrived in the wake of the Gettys, ostensibly to revive the crumbling Palais de la Zahia, but the city claimed him instead. Of those early, languorous days, he said simply, “We all moved in to live a kind of dolce vita.” He never left.

At the 18th-century Palais de la Zahia, Willis established the template: a revival of grand, almost-forgotten craft that served as a backdrop for a profoundly modern, hedonistic life. This project alone would echo through his career, as he was later recalled to reinterpret the palace for its subsequent owners, Alain Delon and the philosopher Bernard-Henri Lévy.

In the ochre glow of the city, he found a permission slip the structured West could never offer: the freedom to be both archaeologist and iconoclast, to demonstrate reverence to the past while using its forms for a new, personal scripture.

His design philosophy was, at its heart, an act of respectful but radical translation. He approached the canonical elements of Moroccan architecture as a vibrant, living vocabulary to be conjugated in new tenses. For instance, tadelakt, the slick, waterproof plaster of the hammams. Where tradition saw a utilitarian finish, Willis saw sensuous potential. He burnished it to a soft, skin-like sheen, then, in a stroke of heresy that became genius. He painted in wide, surreal stripes of pale jade and otherworldly orange in his own kitchen—a gesture reminiscent of Memphis, his own birthplace. The intricate gebs (honeycomb plasterwork) he found too fussy, too “mingy,” and used it with severe restraint. The classic tile patterns were respected, but his colour impositions upon the tile-makers were absolute—a sovereign’s decree in the service of a new aesthetic order.

His most compelling projects include that for Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé, he first worked on Dar es Saada, a house of happiness, transforming a rather plain villa into a testament of simple opulence. Here, his genius for scale and serenity emerged through a vast, restrained fireplace sheathed in rectangular pink-glazed tiles, a library with sober woodwork inspired by the Villa Taylor, a 1930s-inspired cedar bed of such pure, elegance it seems to silence the room around it. Willis claimed his greatest talent lay in designing simply, and in these spaces, one sees a profound editing—stripping away the decorative noise to let the fundamental poetry of form and texture sing.

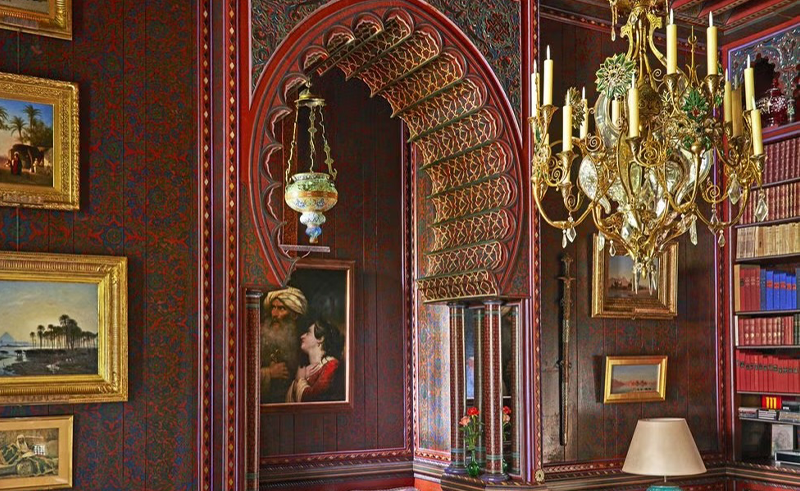

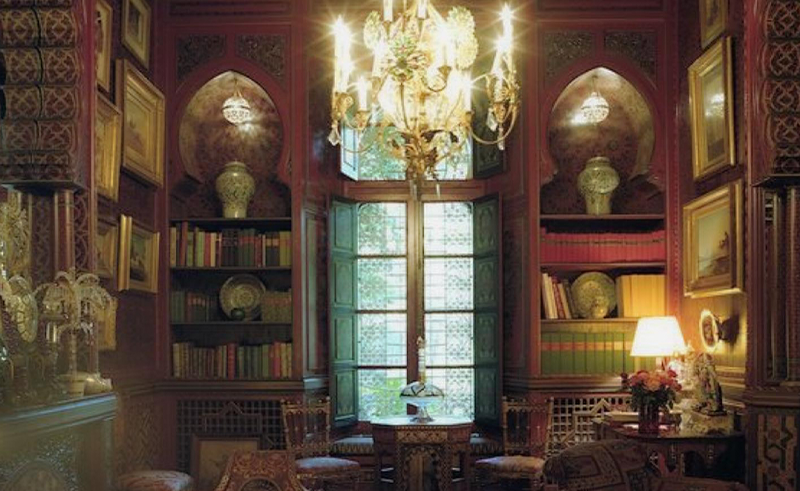

Later, the collaboration expanded to Villa Oasis and the Jardin Majorelle, which Saint Laurent and Bergé purchased to save from developers. Working alongside French designer Jacques Grange, Willis’s translation reached its zenith in the villa’s library—a symphony of carved cedar and glimmering tile that Saint Laurent called his favourite room in the world. For the garden complex, Willis designed the exquisite museum of Berber art within Majorelle’s former studio, a jewel-box that perfectly framed the collection.

Beyond the private palaces of the jet set—which also included a starkly beautiful garden pavilion for Marella Agnelli and a villa for Marie-Hélène de Rothschild—Willis shaped the public face of Moroccan chic. He authored the sensuous, atmospheric blueprint for Dar Yacout, the legendary Marrakech restaurant whose low banquettes and giant lanterns remain iconic. He brought his vision to La Trattoria, Hotel Tichka, and famously recreated the cinematic fantasy of Rick’s Café in Casablanca. Each was a stage set for the cosmopolitan Morocco of the imagination.

And then there was his own sanctuary, Dar Noujoum, the former harem in the medina that served as his living manifesto. It was here, amidst sandalwood-scented rooms jammed with Afghan embroideries and gigantic suede poufs, that the translator’s own desires came home. He rebelled against the typical, narrow Moroccan floor plan, punching through walls to create expansive, square salons that could breathe. In his salon, he finally broke from the local idiom entirely, introducing enveloping European sofas and grand pianos into the architectural lexicon of the riyad. A calculated betrayal, really. “After many years of sitting on squat banquettes at low tables, I yearned for Western comfort. This is it,” as directly reported by his biographer, Marian McEvoy, in the monograph Bill Willis (Éditions Jardin Majorelle).

This personal synthesis, however, was inextricably woven with a famously dissolute personal tapestry. The documentary on his life does not shy from this, painting a portrait of a man as contradictory as his interiors: a creature of impeccable, demanding taste who was also “allergic to discipline,” a charming raconteur who could deliver withering, two-word eviscerations, a visionary whose best work often had to be coaxed out before the afternoon’s first drink. He partied with the Stones, lunched on hashish cookies with Burroughs, and held court in a kohl-eyed, caftan-clad haze. This was the fuel and the foil for his creativity. The louche, languorous life he led was the very atmosphere he was hired to design into stone, plaster, and tile. His greatest professional flaw—a legendary indolence that tried the patience of Rothschilds and Agnellis alike—was the shadow side of his creative insistence: he moved at the pace of his own inspiration, a rhythm out of sync with the metronome of commercial expectation.

In the end, Willis’s legacy is as textured as a tadelakt wall. He is hailed as the man who defined a new design vocabulary for Morocco, a claim substantiated by disciples and style books in his wake. The magnificent monograph by Marian McEvoy, a treasure long hunted only in the Jardin Majorelle bookshop, finally codifies this legacy in lush photographs. Yet his story is also a cautionary melody about the price of such intense, personal fusion. The man who sought and shaped beauty with such singular vision became, in his later years, a reclusive figure, gazing from Dar Noujoum at the neighbouring cemetery, more comfortable, his housekeeper noted, among the dead.

Bill Willis listened to Morocco—to the whisper of its ancient crafts, the geometry of its arches, the glow of its light—and then he translated its stories into a new, intoxicating dialect of luxury and shadow. He taught the world to see Moroccan design not as a frozen artefact, but as a living, breathing language, one capable of speaking about timeless serenity and very contemporary desire in the very same, beautifully translated breath. His work stands as a permanent, gorgeous argument that the most powerful design is about conversation, and that the most compelling beauty often arrives, like the man himself, from the courageous, complicated space between two worlds.