Reblox Crafts Spaces Designed to Come Apart Without Being Tossed Out

An Egyptian architecture studio is rethinking how pop-up spaces are built — and what happens to them after the crowd leaves.

In the event industry, most temporary structures are designed with a short life in mind. Sets go up, crowds arrive, and within days everything is dismantled and discarded. According to architect Dina Soliman, around 70% of pop-up structures end up in landfill after just two or three days of use. That statistic, more than any sustainability buzzword, was the starting point for Reblox.

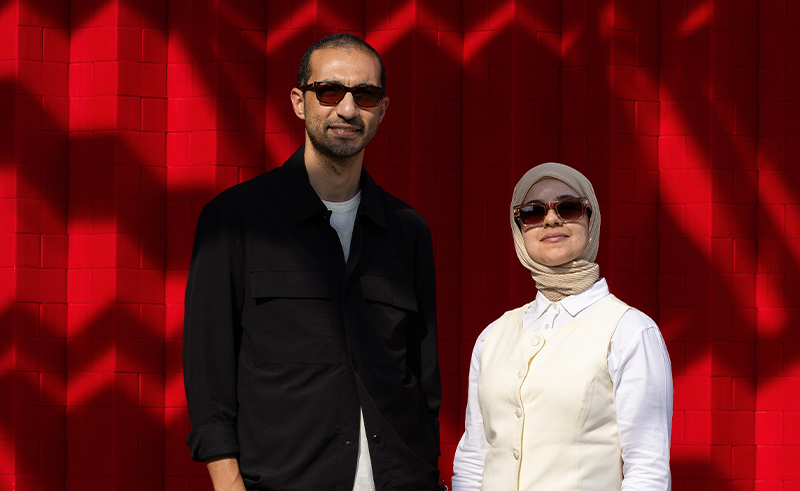

Founded by architects Dina Soliman and Ahmed El Baby, Reblox emerged out of frustration with the build-and-bin cycle that defines exhibitions, activations, and pop-up events. Their response was not a single product, but a system: modular construction blocks made from recycled plastic that can be assembled, dismantled, and reassembled into entirely different forms. The logic is familiar — Soliman likens it to Lego — but the outcome is far more ambitious. Instead of temporary castles or toy cities, the blocks become bespoke exhibition booths, pavilions, and creative installations built to survive repeated use.

Reblox does not position itself simply as a supplier of recycled materials. It proposes a new default for how temporary spaces are designed, produced, and circulated. The system is intentionally minimal: “We have two designs only: a double block and a single block," Dina Soliman, Co-Founder Reblox, tells SceneHome. "With just these two models, you can create an infinite amount of designs and installations.” In the last two years alone, that logic has translated into more than 170 builds, from Cairo Design Week to Rise Up Summit.

Each project begins much like a traditional design commission. A brand arrives with a brief — a product launch, an activation, an exhibition presence — and the Reblox team translates that intent into a spatial concept. Structures are modelled digitally, reduced to an exact parts count and colour palette, and then broken down into modular “packs” prepared at the factory. On site, installation is fast, driven by a standardised set of interlocking units that can expand or contract depending on scale. Once the event ends, the structure is dismantled just as efficiently. If the blocks are rented, they return to Reblox for cleaning and recirculation; if leased, clients can store and reuse them. Any damaged pieces are diverted back into the recycling stream, keeping the material in circulation rather than in landfill.

That closed loop is possible because Reblox controls the entire process. “We have the factory, and we have the moulds, and we design, we produce, and we deliver,” Soliman says. That vertical integration is not just a business decision but a practical one — it allows the system to remain both scalable and responsive.

For recycled-material manufacturers, however, the greatest challenge rarely lies in production. It lies in sourcing raw material that is consistent enough to plan with. Plastic waste often arrives as a mixed and unpredictable feed, varying in colour, grade, and quality. Reblox designed its system around that reality. Instead of relying on complex in-house sorting, the team sources polypropylene from established local merchants, drawing primarily on factory offcuts from furniture manufacturing. The result is a steadier, more predictable material stream that allows for standardisation: a limited set of components produced in volume and adaptable across wildly different briefs.

Sustainability, in this sense, is not just embedded in what the blocks are made from, but in how the supply chain and construction logic have been engineered to be reliable.

The system’s ambitions are perhaps most visible in Reblox’s largest project to date: the Pergola Theatre. Conceived by Cairo-based Cluster Cairo in collaboration with London-based Orient Productions and This Studio, the open-air public theatre required Reblox to deliver two eight-metre towers framing the stage. The project also exposed the realities of working with recycled materials. A red-only palette was requested, but red plastic is simply harder to source in large quantities. That constraint echoed across the collaboration. Very Nile, which worked on the canopy using community-collected plastic from the Nile, faced an even more variable feedstock. The final result — a mix of blues, reds, and whites — became a visible record of what was actually available.

Rather than disguising those limitations, the theatre absorbs them into its design language. It is a community space shaped by material reality, not abstract ideals. For Soliman, seeing the theatre completed and actively used by the local community was one of her proudest moments at Reblox, making the long nights and logistical challenges feel worthwhile.

Elsewhere, unpredictability becomes an aesthetic in its own right. Reblox refers to its mixed-colour blocks as the “marble effect,” created when different coloured feedstocks blend together. “People used to see the mixture of the colours as a defect,” Soliman says, “but now it’s an explicit plus to the design.” In short it has become a visual marker of the material’s recycled origin.

Zoomed out, Reblox sits within a broader cultural shift: waste is no longer something to hide. “In the past years when people started to see end-products made out of recycled materials, there was a paradigm shift,” Soliman says. “Yes, you can make something precious and premium out of waste.” The idea that something premium or desirable can emerge from waste is no longer counterintuitive.

That shift also informs Reblox’s educational work. With both founders coming from academic backgrounds, the company collaborates with universities and design programmes to introduce students to hands-on sustainability. In one initiative, Reblox leased its blocks to American University in Cairo students, allowing them to design and build physically rather than engaging sustainability only through theory. The system lets students feel space, test ideas, and understand material consequences in real time.

This philosophy aligns with a long-standing argument in contemporary design theory. In Cradle to Cradle, William McDonough and Michael Braungart describe environmental collapse not as a failure of materials, but of design systems. Reblox operates squarely within that logic. Its aim is not to produce a single perfect installation, but to create a system that survives teardown, reappears elsewhere, and takes on new forms without ever becoming waste.

The next time you step into a pop-up pavilion or pause inside a temporary installation, Reblox invites a different way of looking. Not as a disposable backdrop, but as a question: where did these materials come from, who shaped them, and where will they go once the lights go out?

Trending This Month

-

Mar 13, 2026