The Fragmented Legacy of Morocco’s Bahia Palace

A palace built in fragments, tangled in power and history, has become one of Marrakech’s most recognizable attractions.

Bahia Palace wasn’t born out of vision or grandeur. It wasn’t crafted as a symbol of power from the start, or even a place designed to last. It grew out of something much smaller, more personal, more tangled. Piece by piece, it was stitched together like a patchwork quilt, a mismatched collection of ambition, scandal and shifting political winds. There was no blueprint. No grand plan. It wasn’t meant to be an architectural wonder, but the weight of history settled into its bones anyway. It’s hard to know where the palace ends and its story begins. They’re layered on top of each other, caught between those walls like the ghosts of Morocco’s past.

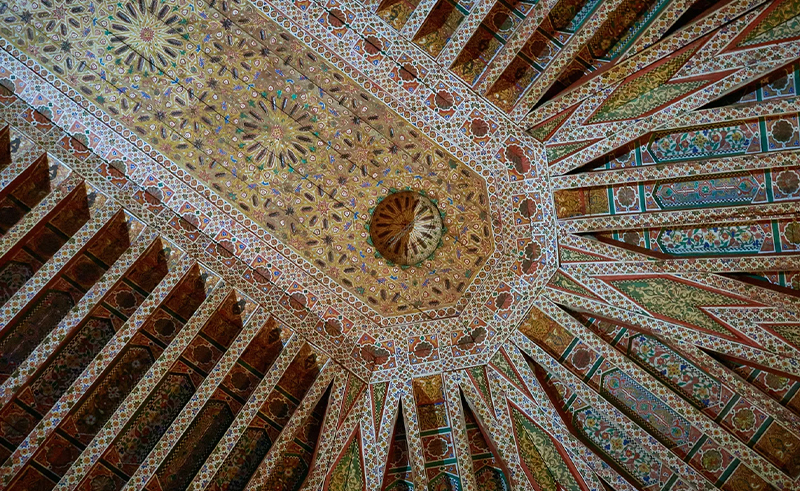

It started with Si Moussa, the Grand Vizier to Sultan Hassan I in the late 19th century. He didn’t set out to build a marvel. His palace was just that - a palace. A residence for his family, something sprawling but functional. As Moussa’s influence expanded, so did the palace. More rooms, more courtyards, more artisans brought in to carve intricate designs into the walls and ceilings. Each new addition added another layer to the growing maze, yet none of it was ever planned. It just kept evolving, changing as the ambitions of those who lived there shifted and grew.

Then came Ba Ahmed, Si Moussa’s son. When he took control as vizier, he didn’t just inherit his father’s position - he inherited the palace too, along with all the unresolved ambitions tied to it. He expanded the palace further, turning it into something larger, more chaotic. Each addition eclipsed the last. No space felt connected to the one before it, no room seemed to fit the layout. Courtyards sprouted up like weeds between halls, and passages twisted in unexpected directions. The palace became a monument to overreach, each brick and tile a reminder of the relentless pursuit of influence.

It was never just about decoration, though the artisans brought in to embellish the palace seemed to take their work as seriously as the palace’s shifting owners did. Every surface told a story, though maybe not the one intended. Stucco flourished with geometric patterns and Arabic inscriptions. Ceilings of cedar wood, painted with flowers and shapes, added bursts of colour in unexpected places. Zellij tiles covered floors in mosaic patterns that drew the eye downward, making it feel as though the ground beneath you was just as much a part of the story as the towering walls. It was all designed to impress, but the effect felt disconnected, as though beauty had been forced into a space that couldn’t quite hold it.

The palace is filled with contradictions. The Grand Courtyard is paved with Carrara marble, imported from Italy, yet it’s surrounded by the warmth of painted wood and zellij tiles from Tetouan. The materials clash, but somehow they coexist, like the different hands that shaped the palace. Some spaces feel grand, open, and full of light. Others feel almost claustrophobic, the halls narrowing to tight passageways that lead to hidden chambers. In the Small Riad, lambrequin arches frame the garden, their delicate symmetry standing in stark contrast to the disordered layout of the palace. It’s a place that never lets you forget its piecemeal construction, a palace that reflects not just the artistry of Morocco but the ambitions, secrets and power struggles of those who once called it home.

And then there’s the history, the stories that unfolded inside its walls. By the time the French Protectorate took over in 1912, the palace had already been the backdrop for years of political intrigue and shifting allegiances. The French used it as offices, another layer added to its growing history. They moved through its chambers, leaving their own mark as colonial powers often do. But the palace remained, enduring, absorbing these moments into its walls as though it was always waiting for the next chapter.

Yet, despite the grand scale and the political power tied to its name, Bahia Palace feels intimate, almost unnervingly so. Walking through its halls, you’re struck by how personal the spaces feel. Large chambers where concubines once lived, rooms that seem to close in on you the deeper you go. The corridors are narrow, winding through the palace like veins, twisting between public courtyards and private spaces. The layout feels like a labyrinth, designed to make you lose your way.

It’s not a palace meant to overwhelm with its beauty. It’s a place that reveals itself slowly, in fragments. A place that doesn’t let you forget the hands that shaped it, the ambitions that twisted it into the disjointed structure it became. The grandeur is there, but it’s in the details - the sharp lines of the carved stucco, the patterns in the zellij tiles, the unexpected colour of a painted ceiling. These details speak of control, of power, of something constantly on the verge of slipping away.

Bahia isn’t a monument to a single vision, but to many visions, layered and intertwined. It’s a palace built from pieces of different lives, each one trying to outdo the last, but in the end, the pieces never quite fit. The result is a place that feels unfinished, and maybe that’s the point. Bahia wasn’t meant to be whole. It was meant to remind us that nothing ever is.

- Previous Article The Enduring Charm of Jeddah’s Old Town of Al Balad

- Next Article The Brilliance of Basuna Mosque by Dar Arafa Architecture

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026