Kairouan's Great Mosque is a Monument Born From Rubble & Resilience

From conquest to rebirth, the Great Mosque of Kairouan is a timeless symbol of faith, endurance and architectural brilliance.

In the vast history of religious monoliths, few places have endured the trials of capture and control as fiercely as the Great Mosque of Kairouan. With its founding fixed in 670 AD at the hands of the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi, its history is one of expansion and endurance.

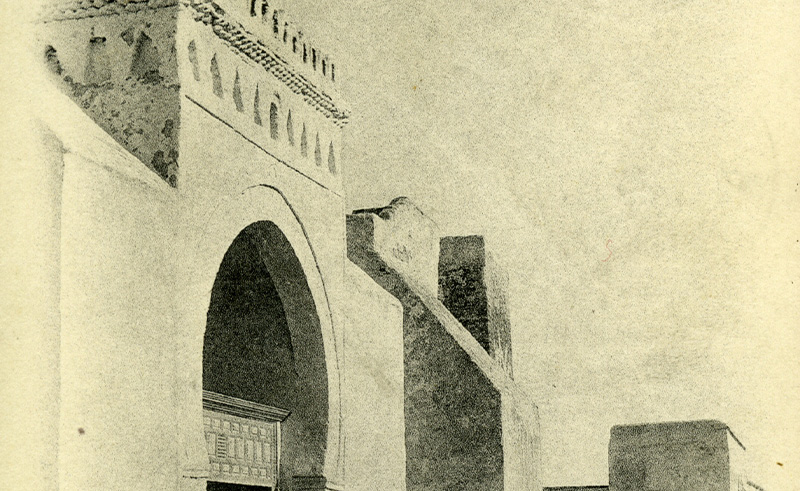

The mosque was first destroyed during the Berber occupation and later resurrected under the Umayyad Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik between 724 and 728 AD. Despite being rebuilt almost entirely, a single relic of its original form remained - the mihrab. As the minaret began to rise, the mosque slowly assumed its present shape. By 774 AD, the Abbasid governor Yazid ibn Hatim had left his mark, further complicating and enriching its architectural layers.

Under the Aghlabids, however, the mosque found its true identity. In 836 AD, Emir Ziyadat Allah I ordered a reconstruction that would define the mosque and its identity for centuries to come. The ribbed dome over the mihrab, rising carefully on squinches, became the focal point of this transformation. Over time, rulers added more elaborate touches - a north-facing bay, a cupola over the portico and double galleries lining the courtyard. By the close of the ninth century, the mosque had transcended its role as a mere building. It stood as a testament to the wealth, power and ambitions of those who had shaped its evolution.

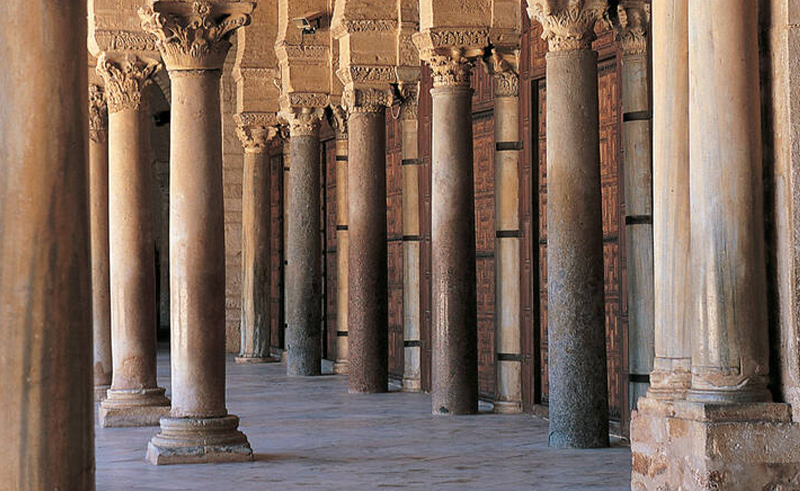

Entering through one of the mosque’s nine gates, you step into a vast, open-air courtyard. The expanse of white marble under foot seems eternal. The columns, all of which were plundered from Roman and Byzantine ruins, have been repurposed to support this sanctuary. No two columns are alike, as a close look quickly makes clear. There are columns with Corinthian capitals, and others that are Ionic. At the centre of the courtyard, an unassuming sundial decorated with a delicate naskh script sits, counting the seconds.

Moving toward the prayer hall, you are met by 17 carved wooden doors. Beyond them lies the hypostyle hall, a space that is expansive and intimate all at once. Light filters gently through the small hanging lamps to cast a soft glow on the 414 columns inside - each a unique cut of marble, granite or porphyry. The world-famous mihrab shimmers ahead with 139 lusterware tiles. Above it, a half-dome of bentwood arches, intricately detailed, reaches skyward.

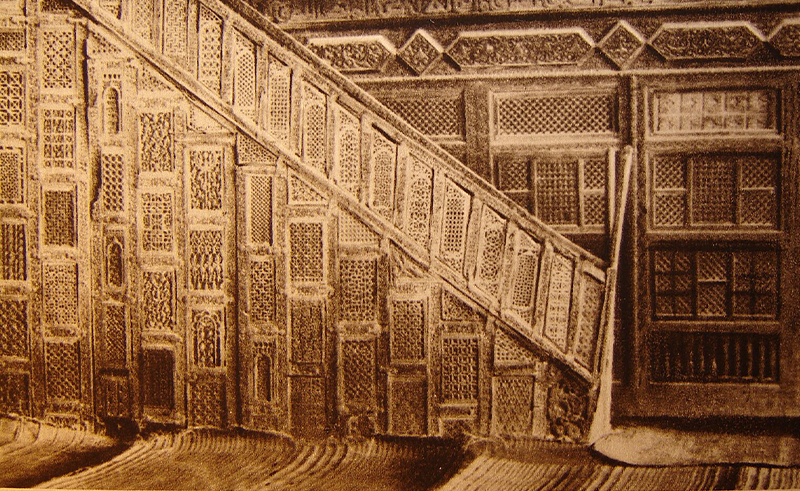

And there, resting quietly, is the minbar - the oldest one in history still in situ. It was carved from teak wood in the ninth century, but visitors today can see it through a large glass enclosure that shields it from the effects of time.

Here, within the walls of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, the stories of conquest and resurrection, of ruin and rebirth, live on. And in its every detail, the mosque speaks not only to the eyes but to something far deeper - the timeless endurance of a legacy built from both faith and stone.

- Previous Article The Enduring Charm of Jeddah’s Old Town of Al Balad

- Next Article The Brilliance of Basuna Mosque by Dar Arafa Architecture

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026