The Abandoned Architecture of Villa Badran by Gamal Bakry

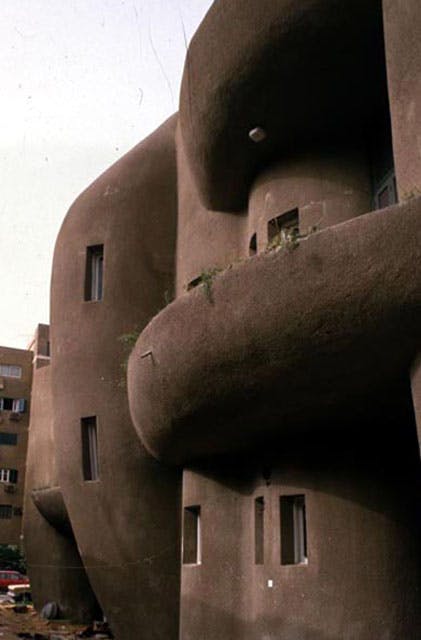

Gamal Bakry’s daringly organic house that got its form from the rise of concrete expressionism during the twentieth century has been abandoned in Mohandessin after a failed renovation.

Back in 20th century Egypt, architecture was thriving, with designers making headlines and engaging the public. These designers shaped Cairo’s urban fabric and informed its visual culture with modernist architecture that followed the concrete expressionism movement, as they were. Yet today, as bulldosing has become an afterthought, these modernist buildings - which aren’t only examples of an iconic style but evidence of a modernising Egyptian society - are carelessly demolished if not turned into freaks of architecture.

While Egyptian architects were exercising modernism by exploring the limits of building materials and technology, none went as far as Gamal Bakry. He's an architect who defied the rigid geometry that was consistent in 1960s modernist buildings by creating a chubby rebellion in the form of Villa Badran, which he built in 1971 on the intersection of Sudan and Yemen St. in Mohandessin.

While Egyptian architects were exercising modernism by exploring the limits of building materials and technology, none went as far as Gamal Bakry. He's an architect who defied the rigid geometry that was consistent in 1960s modernist buildings by creating a chubby rebellion in the form of Villa Badran, which he built in 1971 on the intersection of Sudan and Yemen St. in Mohandessin.

Similar to how designer Ed Benedict dreamt up the prehistoric Flintstones universe from pure imagination, Bakry delved deep into his consciousness to create a piece of peculiar architecture. Some may find Villa Badran ugly, and others appealing, but carried within its curvy and free-flowing facades are thoughts of a not too distant past nonetheless. That was until it was partly destroyed in an attempt to establish a restaurant, and then abandoned.

Similar to how designer Ed Benedict dreamt up the prehistoric Flintstones universe from pure imagination, Bakry delved deep into his consciousness to create a piece of peculiar architecture. Some may find Villa Badran ugly, and others appealing, but carried within its curvy and free-flowing facades are thoughts of a not too distant past nonetheless. That was until it was partly destroyed in an attempt to establish a restaurant, and then abandoned.

-e95a4f0a-9421-4a15-a34d-5632336ca0d8.jpg) To understand why that was its fate, one must look into modernism in Cairo through a slightly broader lens. After all, cities are archives and buildings are documents of cultural and political significance. We design and build them and, unfortunately, at times justify destroying them. Whether by tearing them down to make room for ‘new opportunities’ or ‘adapting’ them with ill-advised renovations, we would be committing aesthetic forgery at least or annihilating chunks of history at most.

To understand why that was its fate, one must look into modernism in Cairo through a slightly broader lens. After all, cities are archives and buildings are documents of cultural and political significance. We design and build them and, unfortunately, at times justify destroying them. Whether by tearing them down to make room for ‘new opportunities’ or ‘adapting’ them with ill-advised renovations, we would be committing aesthetic forgery at least or annihilating chunks of history at most.

Cairo’s Northern Cemetery, also known as The City of the Dead, was recently impacted by a highway construction, which damaged mausoleums belonging to notable twentieth-century figures. This mirrored the fate of modernist architecture – the prevailing style of that period – in the city of the living.

Cairo’s Northern Cemetery, also known as The City of the Dead, was recently impacted by a highway construction, which damaged mausoleums belonging to notable twentieth-century figures. This mirrored the fate of modernist architecture – the prevailing style of that period – in the city of the living.

Beyond the parameters listed by UNESCO as historic and aside from what authorities register as monuments, there’s plenty of heritage disappearing. As the Mexico City-based independent curator Mohamed El Shahed states in his title Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, “demolition of Modern buildings in Cairo began in the 1970s, with pace increasing progressively in the 1990s and monstrously in the 2010s.”

Beyond the parameters listed by UNESCO as historic and aside from what authorities register as monuments, there’s plenty of heritage disappearing. As the Mexico City-based independent curator Mohamed El Shahed states in his title Cairo Since 1900: An Architectural Guide, “demolition of Modern buildings in Cairo began in the 1970s, with pace increasing progressively in the 1990s and monstrously in the 2010s.”

This includes the likes of the landmark villa commissioned by Umm Kulthoum to be built in Zamalek, which was demolished a decade after her passing. These buildings not only need protection, but a complete refamiliarization. Maybe, with enough care, their ‘touristic value’ would be discovered. Here’s the case for Villa Badran.

This includes the likes of the landmark villa commissioned by Umm Kulthoum to be built in Zamalek, which was demolished a decade after her passing. These buildings not only need protection, but a complete refamiliarization. Maybe, with enough care, their ‘touristic value’ would be discovered. Here’s the case for Villa Badran.

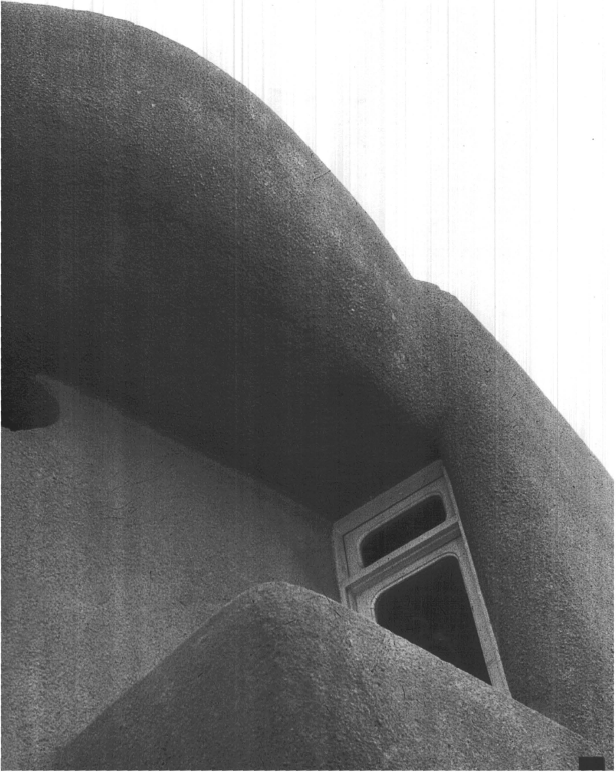

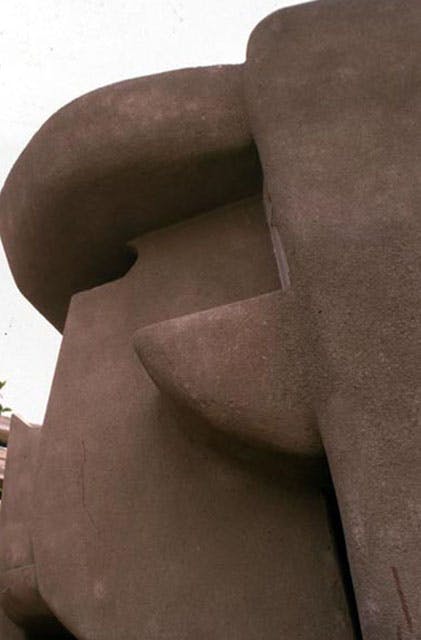

Villa Badran was designed with curvilinear forms, in non-architectural English, those are curves with the extremely occasional straight line. Bakry titled his design ‘A Flexible Composition of a Spatial Melody’; he wanted to stimulate the rural Egyptian building style by using reinforced concrete as a building material rather than mud.

Villa Badran was designed with curvilinear forms, in non-architectural English, those are curves with the extremely occasional straight line. Bakry titled his design ‘A Flexible Composition of a Spatial Melody’; he wanted to stimulate the rural Egyptian building style by using reinforced concrete as a building material rather than mud.

This gave him the flexibility to create fluid forms that offered a unique architectural expression and orchestrated spatial melodies indoors.

Appearing to be arranged randomly, the house is playful. It may look disorienting to a set of eyes used to commit blocks, but it has a considerate living environment. The facades organise the interior into spaces that don’t have a single wasted corner. In fact, one could argue that it has no corners at all.

Appearing to be arranged randomly, the house is playful. It may look disorienting to a set of eyes used to commit blocks, but it has a considerate living environment. The facades organise the interior into spaces that don’t have a single wasted corner. In fact, one could argue that it has no corners at all.

-0c95d89c-9695-44c7-9c2a-f7d81075a5f0.jpg) The ground floor features a garage, terrace, and a generous garden. The first floor hosts the living rooms and lounges, with a terrace to view the greenery below. Concealed behind the curved walls are an office and three bedrooms, leaving the kitchen and bathrooms on the top floor. Each space enjoys its own ventilation, with natural light beaming through thoughtfully placed openings.

The ground floor features a garage, terrace, and a generous garden. The first floor hosts the living rooms and lounges, with a terrace to view the greenery below. Concealed behind the curved walls are an office and three bedrooms, leaving the kitchen and bathrooms on the top floor. Each space enjoys its own ventilation, with natural light beaming through thoughtfully placed openings.

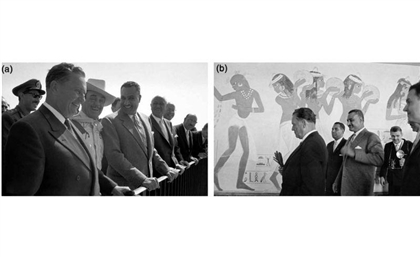

-8a4d3213-6e7e-426b-9017-9957e6c9ca53.jpg) Bakry studied architecture in Egypt and then urban planning in the Netherlands, which developed in him a deep understanding of the contribution architects have to cities and their dwellers. Remembered as a pioneer among Egyptian architects, he was also a prolific writer, and an accomplished graphic and furniture designer. Bakry wasn’t at all shy in making his stance in the face of trends.

Bakry studied architecture in Egypt and then urban planning in the Netherlands, which developed in him a deep understanding of the contribution architects have to cities and their dwellers. Remembered as a pioneer among Egyptian architects, he was also a prolific writer, and an accomplished graphic and furniture designer. Bakry wasn’t at all shy in making his stance in the face of trends.

While designing the villa 52 years ago, he began to map out the rationale behind its architecture. Luckily, Bakry left some notes in 1970 describing his approach as a notion that jumped out at him, one that he wasn’t able to control:

“What comes after 45 years of architectural trials? After 45 years of architectural trials I assume that I design spontaneously, conscious of imitation. Neither inability nor failure, but awareness of popular melodies that passed throughout time and became heritage for everyone. Beyond criticism. Absorbed in our unconsciousness, not leaving our individual domains. The ideas I’m exploiting are not all trials of 45 years. They are attempts to understand the contemporary urban needs of my society. As I stated, I act spontaneously yet consciously.” At some point in the recent and murky past, during decades of neglect, Villa Badran was turned into a restaurant. The process of this ‘transformation’ led to the demolition of some of its parts and the complete defacement of its facades. Fancy some salt on the wound? It’s now abandoned.

At some point in the recent and murky past, during decades of neglect, Villa Badran was turned into a restaurant. The process of this ‘transformation’ led to the demolition of some of its parts and the complete defacement of its facades. Fancy some salt on the wound? It’s now abandoned.

While Egypt’s design industry is unquestionably flourishing in its contemporary renaissance, one question remains inevitable. Will Egypt’s modern architectural past ever be revisited, if not revived?

- Previous Article The Enduring Charm of Jeddah’s Old Town of Al Balad

- Next Article Downtown Cairo's Iconic Cinema Radio Gets Gorgeous Gatsby-esque Revamp

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026