When Cities Were Built for Pigeons: Dovecotes Around the Middle East

From clay towers to city rooftops, the overlooked architecture of pigeons.

Before pigeons were shooed from balconies and sidewalks, we designed entire cities around them. Throughout the Middle East, mudbrick towers line rural landscapes, telling a story of a time when human infrastructure was centred around the flight, return, and survival of pigeons.

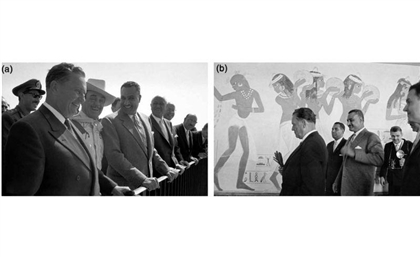

Today, Cairo’s skyline is dominated by makeshift wooden structures rising from rooftops. Peer a bit closer and you’ll see these inhabit one of Cairo’s most storied citizens: pigeons. Their keepers are devoted. Often living right below them, they transform entire rooftops into carefully organised environments for eating, sleeping, breeding, and flying. For some, pigeon keeping is a source of income; for many others, it is a long-held hobby, passed down through generations of families and neighbourhoods. Ever since humans discovered that pigeons reliably return to the place where they were born, the relationship between our two species has been remarkably intertwined. In Egypt, this bond can be traced back to antiquity: pigeons were kept in the Pharaonic period for food and communication as far back as 5,000 years ago. More broadly, pigeons have been used to dispatch letters, take aerial photos of battlegrounds during war, send military commands during the Second World War, and fertilise agricultural land through their droppings.

Modern innovations, however, have slowly forced pigeons into an early retirement. From computers to drones and radios, technology has cut into pigeons’ usefulness. In many Western cities today, pigeons are perceived as pests or as symbols of urban decay. Here in Cairo, and throughout much of the Middle East, this perception never fully took hold. The dovecote towers of Egypt, Iran, and the Gulf reflect the urge to fill landscapes with architecture that accommodates pigeons rather than excludes them, integrating them into the fabric of our communities.

These towers are beautiful: ventilation holes and nesting niches carved directly into their walls are arranged in dynamic and often ornamental patterns. But, why were such modest structures afforded so much architectural care? Why are homes for pigeons treated differently from cattle barns or sheep stalls? The answer lies in the intimacy of our shared history. Pigeons have lived alongside humans not simply as livestock, but as companions, messengers, and co-inhabitants of our everyday surroundings. So, let’s take a closer look to see how these birds have shaped architecture across the Middle East, across time, and throughout history.

Siwa — Egypt

Before reaching the rooftops of Cairo, pigeon keeping was already embedded in Egypt’s rural landscape. This can be seen in Siwa, where white dovecotes are sprinkled throughout the oasis.

Architects from all over the world make the pilgrimage to marvel at these unique pigeon towers. Constructed from kershef - a material made from a blend of salt from the Siwan lakes, clay and sand - the dovecotes are a clear example of architecture shaped by the environment. The clay moderates interior temperatures by absorbing heat during the day and releasing it slowly at night, while the salt acts as a natural binder, strengthening the walls and protecting them from moisture. The result is a form of sustainable, low-maintenance architecture: constructed from local materials while sustaining regional farming practices.

The towers of Siwa are full of architectural character: lined with patterned holes that allow for ventilation and access. Despite their ornate beauty, they are also active agricultural infrastructure. In Siwa, households that keep pigeons gain access to guano - the birds’ droppings - which has long been used as a highly effective organic fertiliser. Rich in nitrogen, guano nourishes crops without the need for synthetic chemicals, creating a closed and sustainable system where bird life directly supports agricultural productivity. By designing spaces that encourage pigeons to return and stay, farmers sustain both their land and their livelihoods.

Of course, pigeon is also a delicacy in Egypt. Hamam mahshi, or stuffed pigeon, is a celebrated dish, revealing a local economy that is centred around pigeons in every sense.

Isfahan — Iran

Between the fifteenth and seventeenth centuries, during the height of the Safavid Empire, the city of Isfahan built over 3,000 dovecotes. While only 700 remain today, these structures testify to a time when pigeon-keeping was essential to the functioning of the city’s ecosystem.

Safavid dovecotes were designed with efficiency in mind: to maximise the number of nests while using the least amount of material. The largest towers can reach up to 18 meters in height, and can house as many as 5,000 nests. The safety of the birds was key in designing these structures. Small windows were placed on an outer drum of the building, high enough to divert predators from the ground and small enough to keep eagles, crows, and owls out. Sometimes frankincense and pepper plants were used to create an odour that would repel insects and pests.

Internally, the towers were designed to encourage return and nesting. Honeycomb divots in the walls provided a safe, dark space for the birds to nest, while a central well provided easy access to water.

The towers were typically made of mud, clay, and adobe: widely available in the region and well-suited to the climate. The mud and clay walls would regulate the internal temperature of the towers, keeping them cool in the summer and warm in the winter. Occasionally, sun-dried brick was used in construction. This material gives us an interesting hint about the level of care communities bestowed upon this precious pet: without periodic maintenance, these materials would deteriorate within a century. The fact that these towers have survived for over 700 years, and are still going strong, speaks to a tradition of continuous human care.

Ad Dilam — Saudi Arabia

The dovecotes of Ad Dilam in Saudi Arabia are some of the most visually striking examples of pigeon architecture in the region. Fourteen towers stand side by side, in rows connected by slender wooden perches that extend like branches from their mudbrick bodies. Their walls are punctured with ventilation and entry holes arranged into stars and geometric constellations. When light shines through, it’s as if these towers come to life.

Although no longer tended to by people - marked by graffiti and rubble - the towers remain inhabited by pigeons and other birds. Historically, pigeons provided these communities with food (meat and eggs), feathers for bedding, guano for fertiliser, and finally, status. In traditional Saudi society, wealth and status could be measured by the number and height of a family’s pigeon tower; the more a family owned, the more wealth they earned, and therefore the higher status they were afforded.

Meybod — Iran

The dovecotes of Meybod, constructed during the Qajar Dynasty roughly 200 years ago, represent a continuation of this tradition. Capable of housing up to 4,000 pigeons, these towers have recently been carefully restored.

Like their Safavid predecessors, Meybod’s dovecotes prioritised safety. Rounded outer walls made of brick are coated in a layer of smooth plaster, which prevented snakes from scaling the tower, while a stone base kept rodents away. Entry for pigeons is limited to a series of openings located in a small central minaret on the roof of the building.

Inside, pigeons would live and nest in small 20 × 20 cm holes in the walls, arranged in alternating rows. Wooden railings on the towers’ second level suggest frequent visits by guano farmers and pigeon-keepers.

Guano had many uses in Iran beyond fertiliser. The nitrogen in the droppings was filtered into potassium nitrate for gunpowder, and the ammonia content was used in leather tanning, making pigeons useful not only in nourishing crops and life but also in sustaining Iran’s economic and industrial systems.

Unlike the dovecotes of Isfahan, the Meybod towers have no windows on the main body of the building. Instead, a large opening at the top lets in a steady stream of light. Because pigeons don’t see well in the dark, this is a crucial aspect of the tower’s design.

Katara Pigeon Towers — Qatar

Off the coast of Doha, the Katara Cultural Village offers a curated reconstruction of both local and regional heritage. It is no surprise, given what we now know about pigeon-keeping, that there are dovecotes in this heritage village. In 2019, heavy rains damaged two of the five towers, collapsing one entirely. In 2022, it was announced by the General Manager of the Katara Cultural Village that the towers would be demolished entirely and renovated with “higher engineering standards”.

These pigeon towers reinterpret an ancient architectural design through a contemporary cultural lens. While they are largely symbolic rather than functional, designed for education and tourism rather than agricultural use, birds can still be seen perched on the wooden beams. Constructed from mud and punctured with small openings for birds to come and go, the Katara pigeon towers echo traditional forms of this architecture. What differentiates these from the Iranian or Saudi towers is the slanted interior walls, which would have allowed the guano to drop cleanly onto the ground making it easier to collect.

Capable of housing up to 14,000 pigeons, the Katara towers recall a long regional history in which pigeons were essential to daily life - used for communication, fertiliser, and food. In Qatar and across the Gulf, pigeon-keeping remains a widely practiced hobby, sustained by both affection and tradition.

Today, the pigeon towers of Katara are maintained with care; sustained by surrounding communities, and celebrated by visitors and tourists who come to see them.

Mit Ghamr — Egypt

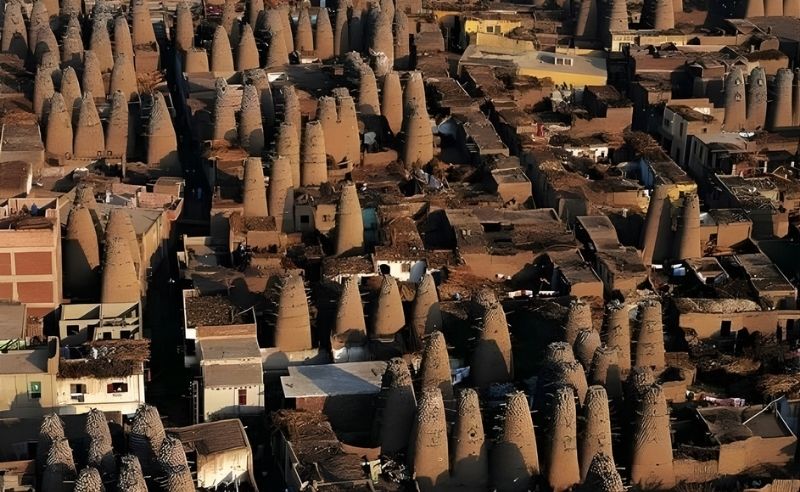

North of Cairo, in the Nile Delta town of Mit Ghamr, dovecotes are interspersed between farmland and homes. In a city of low-built buildings, these 10-15 metre high dovecotes earned the name “clay skyscrapers”.

Unlike the more solitary or scattered pigeon towers of Ad Dilam or Isfahan, these dovecotes are embedded in daily life. Built by farming families, these towers play a vital role in agriculture, with each tower capable of housing thousands of birds. Like the Katara dovecotes, a slight outward slant towards the bottom of the tower helps to collect guano at the base.

The mud walls allow the structures to be extremely low maintenance, keeping temperatures cool and withstanding the hot climate. While the families have to build these towers, the pigeons do the rest of the work themselves. By providing a space for them to safely nest, breed, eat, and sleep, this care is reciprocated by what the pigeons give back.

When these families come to Cairo, they keep this tradition alive in the form of wooden rooftop structures. While they may not use the guano for fertiliser, often with no land to use it on in the city, they practice an ancient pastime by maintaining this relationship with pigeons. In the city, this practice exists among brick blocks, satellite dishes, and makeshift wooden homes painted in bright blues and reds.

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026