The Ageless Mud-Brick Fortress of Aït-Ben-Haddou

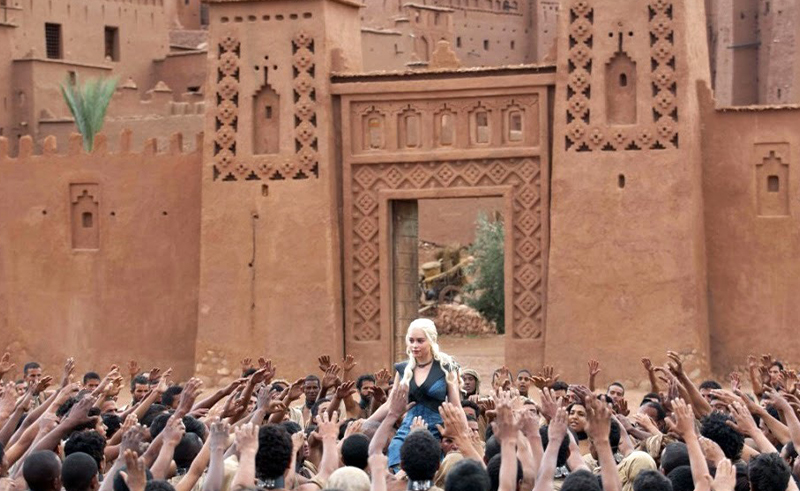

Aït-Ben-Haddou stands as a testament to resilience—its sun-dried walls shaped by trade, migration, and time, immortalized not just in history, but on-screen in Gladiator and Game of Thrones.

For centuries, Morocco’s Aït-Ben-Haddou was more than a waypoint along the trans-Saharan trade routes—it was a thriving nexus of commerce, culture, and architectural ingenuity. A bridge between Marrakech and Timbuktu, it served as a refuge for traders, a fortress against the desert’s harsh elements, and a canvas for the vernacular craftsmanship that defines North African earthen architecture. Today, its sun-baked walls stand as a monument to adaptation and survival, an artifact sculpted from the very land it inhabits.

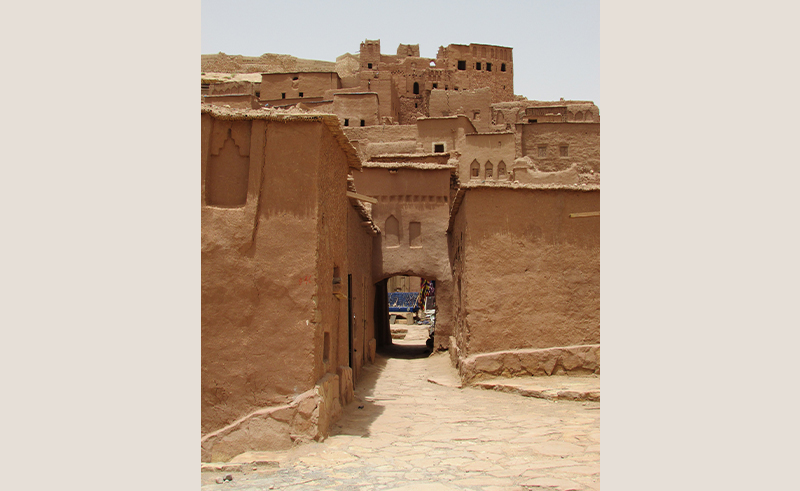

Rising from the slopes of the Ounila Valley, Aït-Ben-Haddou is a striking testament to Morocco's rich architectural heritage. The ksar—a fortified village enclosed within defensive walls—is built using pisé (rammed earth) techniques, where a blend of clay, straw, and water is pressed into molds and left to dry under the unrelenting desert sun. The result is a landscape that appears to be carved directly from the earth itself, shifting in hue from ochre to deep red as the day progresses. This construction method, an ancient but enduring response to the region's climate, provides exceptional insulation against the searing heat, keeping interiors cool despite the external extremes.

Inside, the ksar unfolds as a labyrinth of passageways and stairwells that wind through multi-storied mud-brick dwellings. The layout is not the product of formal planning but of necessity, shaped by the rhythms of daily life and the need for defense against raids and invasions. Narrow alleys channel the wind, cooling the interiors, while thick walls buffer against both heat and cold. The rooftops, more than mere coverings, serve as functional terraces for drying grains and textiles, extending living space beyond the confines of the walls. Carved wooden lintels and geometric motifs etched into the facades whisper of past prosperity, of Berber artisanship influenced by Saharan, Andalusian, and Mediterranean traditions.

The wealth that once flowed through Aït-Ben-Haddou is evident in the grandeur of some of its structures, where intricate geometric carvings and faded frescoes hint at an era when trans-Saharan trade enriched those who lived within its walls. Yet, as the centuries passed and modern infrastructure redirected economic lifelines, the ksar began to empty. Many families relocated to the adjacent village, built with more contemporary materials and better suited to modern conveniences. Despite this, the ksar has endured, recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, ensuring its preservation as a cultural and architectural landmark.

Maintaining an earthen settlement poses challenges that modern materials cannot fully resolve. The very nature of mud-brick construction means that constant renewal is required; the ksar is not built to withstand centuries of neglect. Restoration efforts, such as those led by CRAterre, emphasize the importance of using traditional methods—applying fresh layers of clay-based plaster to reinforce structures and prevent erosion. Any deviation from these time-honored techniques risks compromising the authenticity of Aït-Ben-Haddou’s architectural heritage.

Yet, preservation is a double-edged sword. Tourism, which has played a vital role in financing conservation, also presents risks. The ksar's role as a backdrop for the likes of "Gladiator," "Game of Thrones," and "Lawrence of Arabia" has drawn crowds from across the world. While this attention has cemented its place as one of Morocco’s most photographed locations, the very act of visitors treading its pathways accelerates the erosion of its delicate earthen structures. Conservationists face the daunting task of balancing accessibility with sustainability—of ensuring that Aït-Ben-Haddou remains a living heritage site rather than a hollowed-out relic.

From its highest vantage point, the ksar reveals its full grandeur: homes packed tightly together, their walls blending into one another as if sculpted from the valley itself. Defensive towers stand at its perimeter, a reminder of a time when the fortress had to guard against more than just the elements. In the courtyards, one can almost hear echoes of the past—the hum of barter, the chatter of travelers, the rhythmic pounding of grains being milled. Aït-Ben-Haddou is not simply a place; it is a palimpsest of history, a site where centuries of human resilience, adaptation, and architectural mastery remain inscribed in every sun-dried brick.

Trending This Month

-

Jan 31, 2026