Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies & the Architecture of Continuity

Egyptian designer El-Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil’s masonry-driven architecture placed Islamic spatial language, craft, and structural discipline into Oxford’s long-established academic landscape.

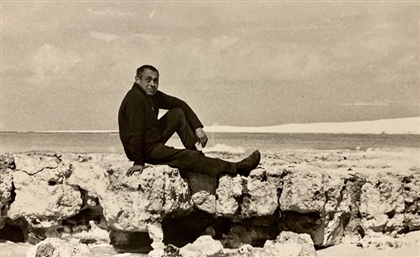

Abdel-Wahed El-Wakil has spent half a century pursuing an argument that never quite settled into the architectural mainstream. His buildings insist that the future can still be made with brick, hand-cut stone and vaults that carry their own weight. The conviction came early, in Cairo, where he trained within the reach of Hassan Fathy’s vernacular modernism and learned that, despite the simplicity of the materials, technique is never neutral. Oxford entered his story late, almost as a kind of test: could this lifelong philosophy hold its ground inside one of Britain’s most scrutinised skylines?

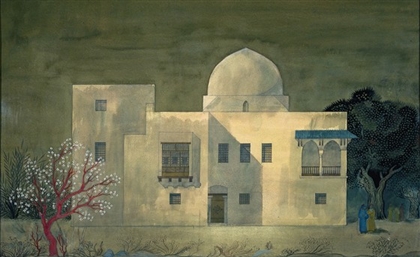

The Centre for Islamic Studies rises on Marston Road with the quiet confidence of someone who has answered that question before. A dome of handmade brick gathers the light; a minaret threads itself into a horizon dominated by college spires; cloisters and courtyards fold into each other. Yet the building’s calm surface belies its stakes. Every choice — masonry instead of concrete, carving instead of cladding, geometric structure instead of engineered shortcuts — comes from principles El-Wakil has defended across continents and decades, even when the profession moved in the opposite direction.

Inside, Oxford becomes a continuation of earlier experiments rather than a departure from them. The plan works through two architectural languages at once: the quadrangular logic of the colleges and an Islamic spatial sequence that turns movement into a kind of narrative. El-Wakil has done this before in houses and mosques from Jeddah to Riyadh, folding local typologies into contemporary needs without theatrics. Here, the negotiation feels more calculated, a compositional patience sharpened by years of refining the same vocabulary.

The friction around the project was predictable. Planning disputes over scale, anxieties about the skyline, questions about cost and time all echoed the resistance that has accompanied El-Wakil’s methods elsewhere. Searching for masons who could shape the stone, sourcing brick that behaved the way he needed it to, working at a pace governed by hand in lieu of machinery — these were the realities of the craft culture he has spent a career protecting. The controversy made visible the clash between two models of architecture: one driven by speed and policy, the other by skill and memory.

What ultimately emerged is a building that neither embraces nor rejects Oxford outright. The mosque anchors the complex with a quiet certainty, while the cloisters, porches and walkways weave the project back into collegiate life. This balance sits at the core of El-Wakil’s work. He avoids revivalism, but he refuses rupture; he treats tradition as a working language rather than a relic.

Seen from within the arc of his career, the Oxford Centre reads like a concentrated version of the argument he has been making for decades. The Tamayouz Lifetime Achievement Award recognises exactly this: a body of work that treats architecture as a cultural continuity sustained by craft, geometry and the people who enact them. Oxford offers a public example of what that position looks like at institutional scale, built slowly, precisely and with a clarity that feels earned rather than declared.

The building represents, finally, a kind of summation. A hand-built manifesto in brick and stone, the product of an architect who has never separated method from meaning. The award may celebrate the man, but Oxford shows the work: the long, deliberate insistence that architecture can still be grounded, local, patient and exacting, even when the world around it insists otherwise.