We Design Beirut Asks: How Can Design Rebuild The City?

For WDB Beirut, design is a way to reconnect people with their city, activate youth, and pull Lebanon back into the global cultural conversation.

It has been nearly two months since We Design Beirut (WDB), the international celebration of design, culture and innovation, unfolded across the Lebanese capital from October 22nd to 26th. Over five days and five distinct locations, the festival drew nearly 70,000 visitors to a series of carefully curated and often interactive exhibitions.

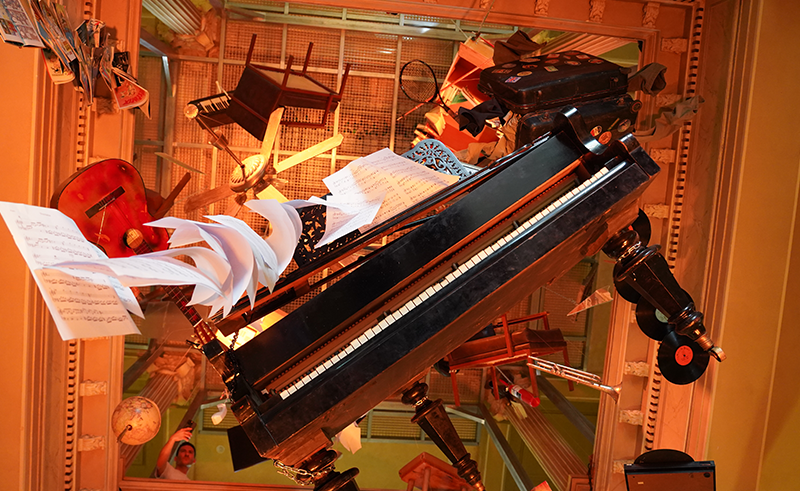

WDB recontextualised art by situating it in unexpected sites across the city, including the Abroyan textile factory, the Civil War-era landmark Burj El Murr, and the modernist Immeuble de l’Union. Additional venues ranged from the manicured lawn of Achrafieh’s Villa Audi to the ancient ruins of the Roman Baths, weaving Beirut’s layered history directly into the festival experience.

The second edition of WDB marked 50 years since the start of the Lebanese Civil War, which between 1975 and 1990 claimed an estimated 150,000 lives, displaced more than a quarter of the population, and left lasting scars on both the city’s buildings and its collective memory.

For many, however, the most immediate chapter of Lebanon’s recent history begins in October 2019, when mass protests erupted across sectarian lines in response to political mismanagement. What followed was a rapid economic collapse: the currency lost most of its value and banks imposed severe restrictions on access to funds. The Covid-19 pandemic deepened the crisis, and in August 4th, 2020, government negligence led to the Beirut port explosion, the largest non-nuclear blast in modern history. The explosion killed more than 200 people and caused over USD 10 billion in damage to infrastructure. More recently, the war between Israel and Hezbollah has continued well beyond the November 2024 ceasefire, with Israeli strikes extending from the southern border to areas near the capital.

This is the context in which WDB was organised and opened, and what gave the event its urgency. Throughout the week, partner Samer Al-Ameen and founder Mariana Wehbe repeatedly emphasised that the “We” in We Design Beirut refers to a collective of designers, artists and cultural practitioners working to reimagine and rebuild the city.

Against this backdrop, a central question emerged:

What is the role of design in rebuilding Beirut, especially when conflict is not a temporary interruption, but a continuous condition?

The WDB team, participants, and exhibitions answered: they said that design is a tool to reconnect people with their surroundings, invigorate youth, and place Lebanon rightfully on the world’s cultural map.

Activating, Not Erasing, The Spaces Around Us

Reconnection was clearest in how WDB reopened abandoned landmarks in Beirut as art galleries. Take the Roman Baths, for example—a site Beirutis walk by often in a busy area of downtown Beirut, but has been inaccessible for years. WDB revived the ancient landmark as the marble exhibition ‘Of Water & Stone’, which asked visitors to develop a new connection with the monument and a sense of care for the site, curator Nour Osseiran said.

In this way, design has the power to reframe what has always been right in front of us, invite us to take responsibility for the space, and decide we belong to it, too.

“Beirut’s abandoned buildings carry layers of history and memory, and design allows us to activate these spaces rather than erase them,” WDB operations manager Kristina Tayar said. “By reusing what already exists, we respect the city’s past while creating room for new life.”

Although, as WDB communications manager Rola Mamlouk clarifies, design does not fix all of Lebanon’s problems, she believes it serves a powerful purpose. “It reminds everyone that creativity is still here, alive, and worth celebrating.”

It’s not only about the site itself; it's showcasing Lebanese talent and craftsmanship within it—particularly young designers.

Design As A Catalyst For The New Generation

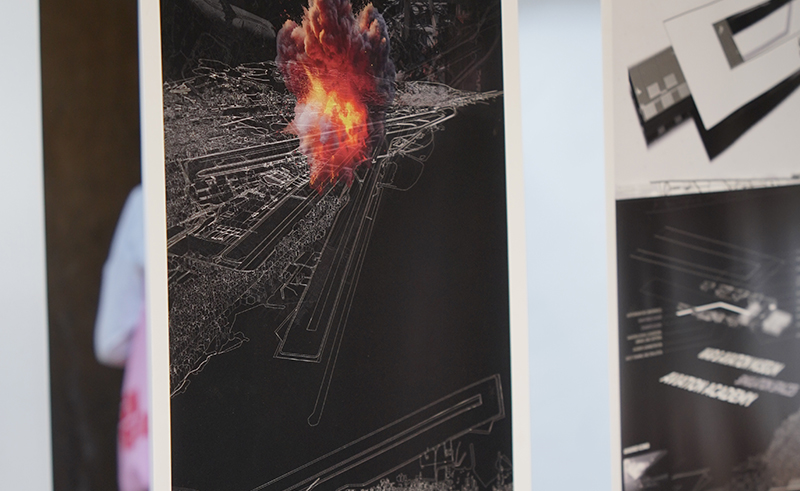

The Burj El Murr student exhibition ‘Design “In” Conflict’, which showcased work by more than 50 designers, offered a clear example of how a Beirut landmark can be reinterpreted through the perspectives of young Lebanese talent.

Construction on Burj El Murr halted in 1975, when the Civil War began, leaving unfinished what was intended to be a 40-storey trade centre. Work never resumed. During the war, the tower’s exposed concrete structure was occupied by militias and snipers due to its strategic position along the Green Line separating East and West Beirut.

Curated by Teymour Khoury, Yasmina Mahmoud, Tarek Mahmoud, and Youssef Bassil, with support from Angela Chiesa and Nicoletta Zakynthinou Xanthi, the exhibition invited students to think of themselves as “first responders” to conflict—not to combat itself, but to life within a continuous cycle of instability. ALBA University student Sleyman Haber presented a human-carrying harness, a partly literal and partly satirical response to the concept of a “human shield.” Marc Khalil, also from ALBA, developed a survival manual centred on repurposing domestic objects during wartime, reimagining a potato peeler as a slingshot and a ladder as a makeshift tent.

“It’s very tiring to have to constantly be ‘resilient’,” Bassil said of a word often used to describe Lebanon and its people, adding that it's time to look for tangible solutions.

‘Design “In” Conflict’ empowered the new generation to share those ideas, revealing how design can generate momentum and visibility among youth in Lebanon. Rae Jill Nassif, WDB Social Media Manager, agreed. She said that as a young woman in Beirut, there is something deeply emotional about how design shapes the city’s recovery.

“It restores dignity, protects identity, and shifts the way people experience the city,” Nassif added. “In a place where many feel stuck, especially the youth, design becomes a push forward helping people picture a better version of the city, giving them tools to act on it. Even small interventions can spark confidence, collaboration, and a new energy.”

Placing Lebanon Firmly On The World’s Cultural Map

For some, WDB marked their first trip to Lebanon and their first time seeing Beirut’s arts and culture scene.

Italian photographer Rosella Degori fell in love with the city during WDB, adding that an event like WDB is vital to placing Lebanon on the global design stage.

“It provides an essential platform for cultural representation, which is paramount in shaping how a country is perceived internationally,” Degori said. “This perception, in turn, shapes views of it, even politically.”

American journalist Jack Balderrama Morley also visited Lebanon for the first time to cover WDB. He didn’t know what to expect, but by the end of the week, he left in awe of Lebanon’s culture, history, and design scene—a narrative that challenges headlines about Lebanon that are dominated by war. WDB offered a refreshing and different kind of global attention.

"The reemergence of Lebanon’s design events is a beacon of interest for the international community,” director of WDB Suhad Shtayyeh said.

WDB felt not only like a site of international exchange, but also like a moment of return, drawing members of the Lebanese diaspora back to Beirut. Many of the press, designers, and organisers involved had roots in Lebanon but were based abroad, reflecting how difficult it has been to remain in the country over the past six years. Since 2019, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese have left, including many young people and professionals, contributing to a large-scale brain drain that has depleted not only the country’s human capital, but its cultural capital as well.

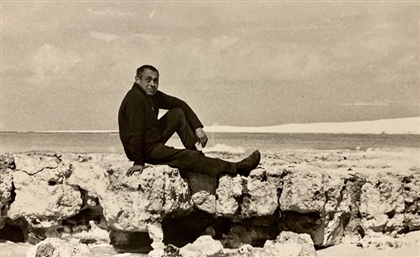

Lebanese architect Ramy Boutros, who participated in the exhibition ‘Totems of the Present & the Absent’ at Villa Audi, described design as a driver of economic growth and a means of drawing global attention to the city.

“Ultimately, design is vital to shaping Beirut’s soul and ensuring that the city emerges from adversity stronger, more vibrant, and firmly placed once again on the world’s cultural map,” he said.

WDB highlighted the capacity of design to reimagine, reinvigorate, and rebuild Beirut. At the same time, it served as a reminder of something fundamental: Beirut was never waiting to be brought back to life—it has always been alive.

- Previous Article El Gouna Plus: An Integrated Platform for Homes in El Gouna

- Next Article Baghdad Reimagined: A Tribute to Cultural Heritage Through AI

Trending This Month

-

Mar 13, 2026